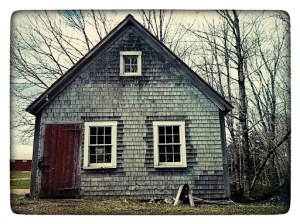

One of my childhood homes, the Motherlode Lodge, burned down a few days ago. It was an old landmark in Alaska. Many, no doubt, have fond memories of visiting the building on the way to ski or hike or pick blueberries in the mountains of Hatcher Pass.

For me, the destruction carries a certain complicated weight. I was there only a year or so before my family went bankrupt and left, but I remember some of that time vividly—partially because I have a habit of collecting devastating memories, but also, Hatcher Pass was just so compelling to me. After all, we’d moved from Nome, near the Arctic Circle, a desolate place devoid of trees or mountains. This new landscape was lush, foreign, and filled with the promise of new beginnings. And maybe all of us were dazzled by the sight of “fool’s gold”—bright mica—that was so abundant in the icy, clear waters of the Little Susitna, the river that tumbled from the mountains down into the valley below.

My mother and my then-new stepfather, a handsome second-generation Irishman from New Jersey, bought the lodge in order to fulfill his dream of running “a real Irish pub.” It was purchased with the entirety of my mother’s retirement savings as well as a hefty chunk of borrowed money.

In the fall, I started Ms. Cavender’s fourth-grade class at Sherrod Elementary in Palmer, down in the Mat-Su Valley. My classmates included Penny (who had a penchant for drawing horses), Robbie (who carried a football-themed lunchbox), Tessa (who always smiled and was, notably, shorter than I), Crystal (who was gorgeous and knew it), and Becky (who was shy and kind and also my closest thing to a best friend). I had a little bit of a crush on Robbie, who probably had a little bit of a crush on Crystal.

My mother taught fifth grade in the same school—many of her students are among Alaska’s movers and shakers now. I remember that was the year J.J., also in my mother’s class, crashed his three-wheeler and tore up his beautiful face. He shattered his arm and, because of the way it was cast (out and up), my mother constantly called on him in class. I remember him well because he often stayed after to make up work missed from all those surgeries; he was the one sweet thread of tentative friendship between that time and some years later, after I moved to Wasilla and then back again to Palmer for high school.

As a girl who’d already gone through two fathers previously, I wanted more than anything to be a part of a “normal” family, what I imagined everyone else had. I unconsciously believed it fell to me to make the relationship with my new stepfather work, and so I became obsessed with Irishness, which was encouraged in various ways. It was a real shame, for my stepfather, that I was a girl—and probably not even of Irish descent at that—but he offered that I could at least better the situation by legally changing my name to Patty. I seriously considered this. He also insisted that I become a proper Catholic, so I spent a lot of time dutifully memorizing “Hail Mary” for my eventual baptism at St. Michael’s in Palmer. Many days, I carefully studied the map of Ireland tacked up in the pub while turning that one Gaelic word he taught me over and over in my mouth like an incantation: “fray-dee” for “potato.”

(Incidentally, some years later in high school, Robbie would ask me, “Hey, aren’t you Irish?” I was mortified that he remembered. By that time, I had a different stepfather and a whole new set of pathologies.)

I couldn’t have friends out to the lodge—not that I had many anyway. My stepfather was an alcoholic, after all. And he ran a bar—a constant, free-for-all party. It was, as my mother once said, “no place for a child.”

So I learned to embrace my exploration in solitude. At that time there was a stand of willow trees on the hill next to the main building—it was leveled in later years to make way for a new addition. This little forest in miniature was a haven, my place to escape from the downward spiral that was our intertwined lives. In summer, I gathered old boards and put together a small shelter and imagined it to be my cabin. In winter, I tracked vole and rabbit prints in the snow. In every season, I’d lie on my back in snow or moss or brush and do what I called “the big-small”—I’d feel myself expanding to the size of the universe, and then I’d shrink back down to a grain of sand. In this way, I think I discovered some sense of spirituality in Hatcher Pass; my way of seeing was my one true magic power.

As for the lodge, I explored that, too. But unlike the natural world around us (rife, no doubt, with dangerous wildlife), there was something about that old, cloying interior and all of its shadows that frightened me. Maybe it mimicked too closely my constant and vivid architectural dreams—the long hallways lined with doors, the unlit crawlspace closets, an eerily large and metallic kitchen, a bar engulfed in smoke and disembodied laughter. And then there was the new addition—not the one that would someday erase my trees—but another to the right of the main structure. It was still under construction when we moved in, and it remained in unfinished limbo for the duration of our time there. That wing had a skin, but inside it was all darkness and bare bones.

My first bedroom in the Motherlode was a closet of a space in the top left of the main structure, at the end of a hall of lodgers’ rooms, most of which remained unrented. It had one window looking out from the side of the building, over the trees and down into the valley below. The window was important to me because in Nome, windows had been a rare luxury. There, I’d had nothing more than a porthole in my bedroom—an eight-by-eight-inch cut-out up high on the wall that could be opened in the summer months to let in fresh air. The new room, in contrast, held a view of vast possibility.

One of my stepfather’s drinking buddies took a liking to that view as well, though, and I was relocated to another room and then another. The latter was adjacent to the new addition. It had a large window, but it looked only inside, into that great, unfinished carcass. I felt that I was always on the edge of being consumed. It terrified me.

Shortly before my move to this last new room, my stepfather invited his sister and her family to come live with us, to help out with the management of a failing enterprise. Her eldest son quickly took up the habit of hunting me with an air rifle in my magical forest, and also picking the lock on the bathroom door while I showered. Whatever safety I felt in my world was crushed. They left a few months after their arrival. And some time after that, so did we. We did not move on to better circumstances. We simply moved on.

Many years after I left Alaska, it was my mother who sent me the newspaper clipping describing how J.J. pulled over his truck one day and took his life on the side of the road. He had been a social worker at the time—a caretaker of the lost. I couldn’t believe that someone with that kind of spirit could be broken. He left behind a wife and three kids. I recognized the name of his wife. We’d all gone to high school together.

I sense there are unseen generations who come of age in Alaska, kids scarred by place and circumstance. We all do our best, like good Alaskans, to “show no weakness.” But sometimes we fail. Even the sturdiest of structures can burn to the ground. And though I want to say that I am one of the resilient ones, the truth is that I’m not. I just got through it, whatever “it” was, and now I’m here.

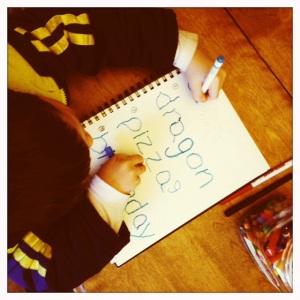

I had hoped that I’d return someday to the Motherlode Lodge with my son and daughter. I’d say, “I used to live here. This place is part of me.” They’d see that big old building surrounded by spectacular landscape, and they’d think I was lucky. I’d be reminded that, in a way, they come from that place, too, and that every bit of my complicated history led me to where I am now. I’d walk with them through a stand of unlikely trees. We’d lie down together on green moss next to a cold, clear river glinting in sunlight. I’d teach them to be so small they almost vanish, so vast that nothing can contain them.